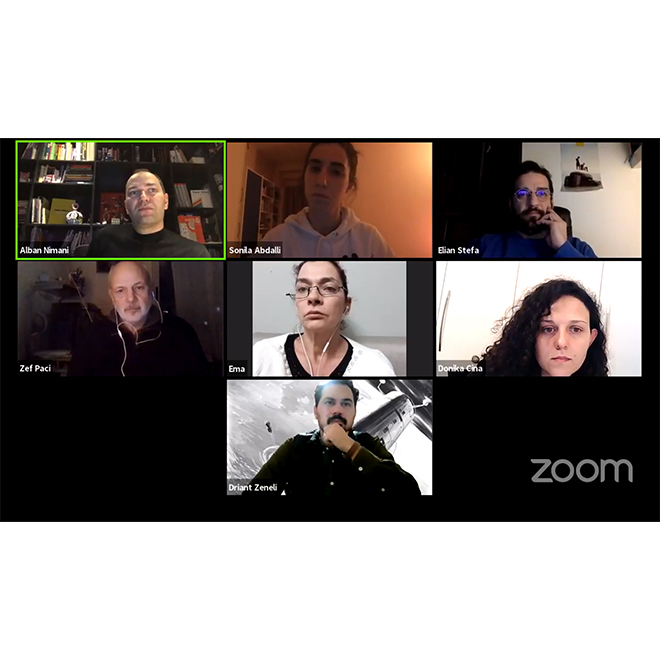

Art and Independent Cultural Institutions during the Covid-19 Pandemic Seven representatives of the Independent Cultural Institutions in Albania met virtually with the invitation and organization of Alban Nimani, Head of “Tulla Culture Center”. They discussed the position of the institutions they administer and the options they have in order to move forward: Will these cultural institutions exist after the reopening? While fighting the closure due to the pandemic and the huge revenue losses, galleries and cultural operators have adapted to new circumstances and protocols, which resulted in innovative online exhibitions, programs through online platforms and drastic reductions in participants.

Are these new forms such as online/streaming temporary, or they’re the new way of communicating in the future?

Are these alternative forms a type of simulation to keep the visual art and the culture alive or are they destroying them?

What is the price of the closure of the institutions?

Which is the direction that the galleries, the foundations and the artists should follow during and after the pandemic?

Could this pandemic be used as a creative catalyst?

What are the main problems that the artists and the independent institutions in Albania are struggling with for their survival?

The Covid-19 pandemic accentuated the need to modify the relationship between the artist and the public institutions, as it reconceptualized the way we live and create. Cultural institutions were closed all over the world, says Alban Nimani, because the pandemic brought significant obstacles for both cultural institutions and artists. The art and the publishing of artistic habits found themselves in need of adapting to security protocols or remaining silent.

Ema Andrea, actress and founder of “MAM Foundation” opened the discussion by emphasizing the specific position of the theater and the importance of initiatives that should follow the dialogue between artists, while expressing the distrust that the needs of the artists will not be properly addressed. While citing examples from her experience, Ema Andrea said that the theater, as a living stage, did not survive the pandemic. It disappeared, because after being transferred to video, with the absence of communication that occurs with the public when the actor performs in front of them, it is no longer called theater, but film or something else.

“Taking the theater out to the streets was a form of survival, yet it is not successful or eternal.”

What the pandemic recalled is the delicate position of independent artists. These are artists whose work is based on projects, supported mainly by international organizations and a few state institutions. While addressing the legal and structural vacuum where these artists operate, according to Ema Andrea, the artists who are not part of a paid structure do not exist. There is a possibility, according to her, that in Albania the problem could derive from the artists themselves and from the way they concept their role, their relationship with society and the institutions. They did not have the opportunity to create a system to function within, because they don’t have a far-seeing vision and their discussions are not deduced into concrete actions.

According to Ema Andrea, the artists need to agree on the principles of their organization and functioning. “They wriggled” is an expression that she uses to indicate the difficulties of the artists during the pandemic and its roots are found in earlier sources such as the lack of regulatory framework and the inability of the artists to get organized and to communicate with the policymakers. Through two questions, Andrea proves the depth of the concern and puts forward some points for future discussions: First, the newly graduated artists, what do they bring home in the evening? Secondly, how can art become saleable in a society whose audience is not ready?

“The artistic principles are affected by poverty and the lack of artistic education of the public.”

Elian Stefa, architect and founder of the space “Galeria e Bregdetit” in Vlora, considers the level of the Albanian art scene as “embryonic”. This means that the Albanian art has been nourished enough to be able to survive, but not to grow. He underlined the need for growth and to formally turn to the state institutions for support under a long-term strategy.

The gallery owners lost their visitors during the pandemic months. This excludes being active on a social network profile, which does not promote art, it does not make the connection between it and the public, it does not include the guide from the curator and it does not enable the purchase, which severely damaged the galleries.

However, there are also cultural spaces that adapted to the pandemic by their nature. Zef Paci, professor of the History of Art and representative of ArtHouse in Shkodra, talked about how the situation led to the deviation of this artistic entity from the previous structure. ArtHouse has been a peripheral structure, not a central one. Although it was formerly supported by the Ministry of Culture, says Paci, it now stands independent and determined with a long-term goal to provide workshops, a film festival (Ekrani i Artit) and a summer school.

“Alternative education is important because the university curricula are reviewed every four years, meanwhile alternative spaces are updated frequently and as a result they are more recent.”

Before talking about how ArtHouse adapted to the new conditions, Zef Paci reiterated the importance of the relationship of art with the state structures and the transmission of the requirements to the Ministry of Culture, which must be applied with dignity and equality. The summer school was dissolved and the film festival was left without participants. Few exhibitions were created accepting a low number of visitors. However, a solution was found with the translation of a group of authors related to the summer school topics, which fostered discussions between artists and art lovers. In cooperation with the EU Regional Cooperation Council, the ArtHouse Channel was created on YouTube, where interviews by contemporary Albanian and foreign artists were published. By strengthening its online presence, ArtHouse kept alive its activity and communication with the public.

Visual artist Driant Zeneli talked about how HARABEL Contemporary, a platform co-founded by him and dedicated to the promotion and archiving of Albanian contemporary art continued to offer “Thoughts” online, a creative project where personalities from the world of contemporary art and culture share their thoughts on life and artistic activity. Like ArtHouse, HARABEL Contemporary chose to rethink the communication with the public. Thus was born the Encyclopedia of Everyday Words, an initiative that sheds light on the etymology of words by linking the image of an artist to a word, which is further explained. Also, Harabel Creative Atelier was created as a school for children where they work with their imagination, drawings and body language. Finally, the intervention in the public urban space begins with the work “Bukurshkrimi” (The Calligraphy) by Adrian Paci, already positioned along the boulevard “Dëshmorët e Kombit”, between the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Agriculture.

Driant Zeneli accentuated the practical importance of the legal organization of artists through the consultation with law experts. If artists were to be organized as a legal entity, their needs would be institutionalized, thus inducing an administrative responsibility for a public response by the Ministry of Culture. Countries of the region bring examples of good interaction, such as the fees that independent artists received in Kosovo. Especially the musicians, says Driant Zeneli, were used to entertain the public during the pandemic, but their intellectual property was not well administered. Digitalization is the main tool for the diffusion of cultural works, however when it is legally unregulated, it leaves room for misuse.

“Artists must achieve legal protection and economic stability through the help of law experts.”

Otherwise, the young artists or those who didn’t have the opportunity to appear in the media and consequently, to be recognized by the public, cannot succeed without a legal status and remain in difficulty to survive financially with their passion.

While talking about the risk of the collapse of some cultural initiatives, others come to life as an impetus to create and increase creative enthusiasm. Such is the “Boulevard Art & Media Institute”, a space within DeStil, conceived by Donika Çina, Sonila Abdalli and Valentina Bonizzi. The boulevard will be a place for creators, endowed with DeStil’s past experience in a new space. The founders were optimistic about its role in creating a community to help the artists and the public.

Independent artists feel that in order to survive, the law needs to regulate their position and career. A strategy dedicated to the culture in Albania would bring a real result for its recovery and revolutionization. The artists’ response needs to be collective, mature and direct, enriched with legal advice and education on normative regulations. Enterprises know the system in which they operate, the legal norms to which they submit to fulfill their role and financial gain. The question remains: in what system do artists operate?